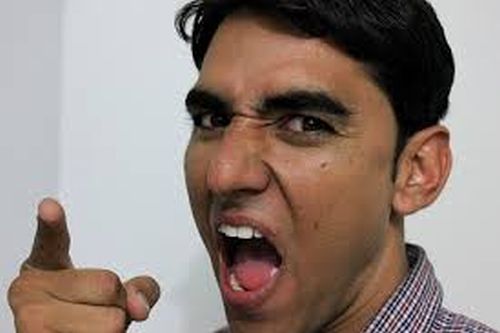

“You don’t have a son anymore!” Those angry words are shouted through the phone, followed by the silence of a severed connection. Somewhere your adult child severed more than just a phone link. He wants you out of his life, forever. Or maybe you’re the one who severed the connection after telling your daughter she was no longer welcome at home. How did it come to this and where do you go from here?

It’s a parent’s nightmare, second only to the death of a child. This is a living death, where your child is still out there somewhere, growing older, moving on, experiencing joy and sadness, perhaps suffering and struggling, all without you. As if your grief weren’t enough, you heap on parental shame; this is at least partially your fault. Your son or daughter blames you for their misery and may be spreading a dramatic narrative among family and friends that casts you as the villain.

The causes of parent-child alienation are as numerous as the cases. “It is impossible to live with another person and not have areas of conflict,” writes family therapist Shauna L. Smith in her book Making Peace With Your Adult Children. “[W]e must deal with differences in appearance, aptitude, intellectual level, physical strength and dexterity, energy, rate of development… Whether someone is the oldest, the only, the middle, or the youngest child may affect how he functions in relationships.” It all adds up to “potential areas of battle if the differences involved are not respected and handled cooperatively.”

In that uncharted journey called “parenting,” you may have stumbled or fallen flat on your face. Or maybe in doing the right thing you set off an overreaction in your immature child that slammed the door between you and them.

- Your son asked for a substantial amount of money and you refused

- You asked your daughter for a substantial amount of money, and she refused

- Your son couldn’t forgive you for divorcing

- You or your spouse put job before family

- Your daughter thought you favored her siblings

- Your son drained the family with his addictions

- Your daughter manipulated and verbally abused you

- Your son became a danger to you or younger siblings

- Your daughter stole from you

- You fell into a pattern of berating your son for his shortcomings

- Your daughter was sexually abused and you missed the signs

- Your son couldn’t wait to escape from dysfunctional patterns at home

- A family move took your daughter away from her friends and she never forgave you

- Your alcoholism or another illness deprived your son of a real parent

- You’re simply worn out by the battle

Maybe you sincerely don’t know what motivated your child. Maybe you’re unable to dig deeply enough within yourself to identify and own a reason for the split. There are sometimes factors that are out of your control. But don’t use that as an excuse. Complete honesty with yourself is essential here. Excuses are the enemy when there is a a chasm between you and your adult child.

This can go one of two ways, depending on how damaging the split is; you can try to make amends, or you can declare a total loss and move on. As gut wrenching as the latter is, it may be necessary to save yourself, your marriage or your remaining children. But before you do that, make sure you have done everything within your power — and maybe a few steps beyond your power — to heal the rift.

Joshua Coleman, Ph.D., author of When Parents Hurt, says some parents give up too quickly and send a subtle message to the child that he or she is not worth the effort, or had no right to complain in the first place. “Continuing to reach out is a parental act,” Dr. Coleman writes. “It’s a demonstration of concern and dedication. It keeps the door open. It humanizes you. It shows that you love your child enough to fight for him even when you’re getting back – literally – nothing but grief.”

Take responsibility. Own your part; stop making excuses. Sincerely express regret for the rift, verbally and in writing. (Regret is not the same as an apology. If you owe an apology, then offer it) Forgive your child. Forgive yourself. Get counseling.

Make sure your child knows the door is still open. If he or she walks through that door, don’t fall into old patterns of criticism, blame and resentment. As gently as possible, set boundaries that both you and the child can rely on to maintain respect between you. Agree to avoid the old conversational triggers. Show genuine interest in the things that make your child happy. Let go of your expectation that they will turn out as you always dreamed they would. Instead, honor their independence and adulthood.

Try to see your offspring the way outsiders do. They don’t have the same emotional investment in the child as you do. They are the ones who don’t quite understand your problem. They see your rebellious daughter as a bright and accomplished woman in her own right. They see your addicted son as a tragic figure in need of empathy and help. Maybe they have a point.

Understand your child’s limitations, be they emotional, mental or physical. Don’t expect them to reason with the wisdom of age or experience. Understand your own emotional baggage that may come from the way you were parented, the dynamics of your marriage, and the stress of your job, your health or other children.

There is not room here to illustrate all the ways you can make amends with your adult child. I recommend studying the advice of experts such as Shauna Smith in Making Peace With Your Adult Child (Plenum Publishing Corp), Dr. Coleman in When Parents Hurt (Collins Living Publisher), and Linda M. Herman in Parents to the End (NTI Upstream Publisher). They offer exercises in self-reflection and examples from others who have walked this road.

Reconciliation may turn out to be a long and demanding process that requires you to be the grown up, tempered with humility, compassion and a real desire to have your child back in your life. If it doesn’t work, then the alternative of leaving your child behind will demand even more from you.

You will go through stages of grief, similar to death. “Your purpose in grieving is not to forget the person,” Smith writes. “It is to integrate the positive things you had together and the lessons you have learned into your current life.” She suggests doing things that you might do if a child died – make a photo collage of the good times, plant a tree or flower garden in their memory, fill a memorabilia box, write a poem, write a letter that you never send expressing your feelings of love and loss, volunteer with victims of the cause that took them from you such as drug addiction or sexual abuse.

As counter-intuitive as it may seem, Dr. Coleman advises parents not to rely on continued words of hope when their child is gone. “I don’t find that kind of happy talk very useful to parents who have already tried everything. It is more likely to leave them feeling shamed, since it implies that they haven’t tried hard enough…[S]ometimes hope is a bad idea, especially if it is based on the notion that we still have significant power to influence our adult children’s lives. At some point we have to accept that they are on their own and, despite our worst mistakes and best efforts, now have to find their own way. We will always be their parents, but our ability to parent, at least in a significant way, eventually ends. At that point, we have to separate the verb from the noun.”

That’s sound advice for parents of adult children no matter what their circumstances.

You don’t want to miss the next installment. Subscribe here to receive email notifications of new posts.